Partnerships and Evaluation

If you are new to following my blog, welcome! My CEL placement is with Theatre Direct, supporting their community-engaged/arts-education project, What Was My Backyard? This new musical for young audiences is designed to tour to elementary schools, with a team of professional artists who rehearse and build the show alongsides students who take active roles in creating and enacting the production. The show tells and responds to this story from the history of the place we now call Toronto. A pilot project took place at the end of January 2020 with 80 grade 4-6's. If you want to find out more about the process, you can read my previous blog reflections on how this participatory process enacts both principals and community-engaged arts and ideal arts education practices.

Placement Update

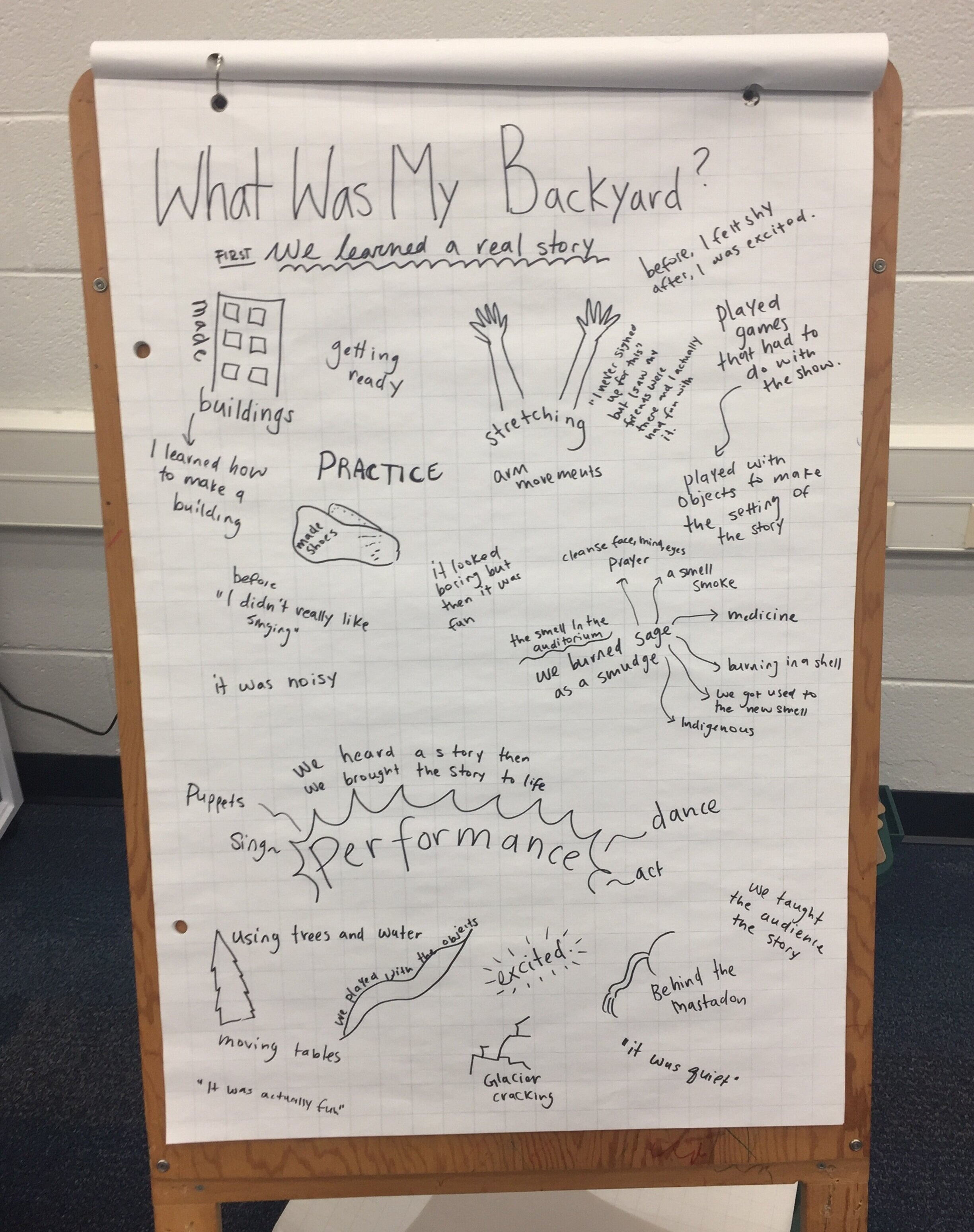

Shortly before practicum started, I travelled with the director of What Was My Backyard? back to the elementary school that hosted the pilot project in January. Part of my placement involved assisting with the design of a series of interactive workshops to collect reflections and evolution on the pilot project. However, due to work actions, the scope of enacting these plans shifted and condensed slightly into this combined session. We met in the library with a small “focus group” of students who had been part of different aspects of the process, along with one teacher. I facilitated activities to invite discussion, responding to the following prompts that we had developed:

What did we do?

What was your favourite part?

What was the hardest part?

What do you wish you had known before we started?

What do you know now?

What do you want to do next?

First I did some live drawing/mapping to capture responses to the first question: remembering what we did. In this pilot, each student had chosen a discipline to focus on (singing, acting, making or dancing), and so, although they had been immersed in their own process, and witnessed the final result, each student had only seen a quarter of the process. We explored responses to the subsequent questions through writing and discussion activities. I also created a teacher survey for participating teachers, and spoke briefly with the Vice Principal.

When partnerships go wrong - or not

One learning goal I have for this placement is to think through ways to build partnerships between arts organizations and schools in meaningful, productive and artful ways. My sense that this is not always straight-forward is informed partially by personal experience, but was reinforced/reflected by a study I encountered (also in an elective!) detailing a collaboration between an arts organization and American public school that, by the accounts of all involved parties, did not end successfully (Quinn & Joseph, 2001). Because my previous two entries have concerned themselves largely with the promise and possibility with the kind of work I’ve seen unfolding as part of What Was My Backyard?, I wanted to pause and return to this article, to think through some of the structural/societal challenges, and how these can be resisted, perhaps, through the model I am observing.

Quinn and Kahne's (2001) case study explores the an arts organization responded to under-funded in-school arts programming by offering after-school arts workshops for kids/youth, that ultimately had to be cancelled because the relationship between the school and the organization broke down. Although the arts program in the article is in practice quite different than Theatre Direct’s, the authors see it as a “best case scenario” (Quinn & Kahne, 2001, p. 17), in which, similarly to What Was My Backyard?, the artists had secured funding, which allowed for time to plan; prepare; work within cultural considerations; hire expert artists; and work in a community in which they had strong ties (Quinn & Kahne, 2001). Of course, I can imagine, if these factors were not able to be in place (as is too-often the case given limited resources for the arts), different conflicts might arise.

In the article's case study, a central challenge was the school administration’s commitment to school being primarily “safe and enjoyable” (Quinn & Kahne, 2001, p. 23). This led to teachers and administration interrupting art-making processes that they saw as disruptive or risky, but that artists saw as necessary to artistic outcomes (Quinn & Kahne, 2001). In my initial journaled response to this article (written for the elective course), I wrote:

“'Safe and comfortable' are not in themselves bad things to wish for children, but where they are put down as authoritative limits to art-making, they are replicating, not disrupting, power structures, and so the transformative possibilities for community-building, and pleasurable, meaningful art outcomes are restricted.” Although I wrote this long before my placement began, it is still something I feel passionately about, and something I was surprised was not a significant barrier to the WWMBY? pilot project.

"Authentically engaging the arts can lead to conflicts with norms of rationality and obedience.” (Quinn & Kahne, 2001, p. 25)

And I do think it must come back to relationships. Because the project was risky:

It brought non-teacher adults into the school, including community volunteers with a variety of high needs and disabilities. It was noisy. It took up space. It invited kids to think critically about colonial structures and narratives. It mixed students across age and classroom groups. It disrupted schedules/routines for three days. These are factors at least as “disruptive” as the activities described in the article: as Quinn and Kahne (2001) point out, in itself, "authentically engaging the arts can lead to conflicts with norms of rationality and obedience.” (p. 25) But, at the pilot school, this didn’t lead to significant tension or a break down. The evaluation revealed a number of ways that long-term relationships nurtured this project's support. In the library, I saw this in action: it was abundantly clear that it was because of the efforts of the projects’ main teacher-ally that the evaluation session was possible at all. And she didn’t just organize the evaluation circle, she stepped into it, took a seat, and joined in the discussion alongside artists and students.

To me, this speaks to another point that struck me from the article: in evaluating the importance of artist-facilitated art-making, the authors write that these in-school, extra-curricular spaces are some of the only time in school that children have “opportunities to forge supportive relationships with adults" (Quinn & Kahne, 2001, p. 12) who are not their teachers. This resonated with a brief evaluative conversation I had with our pilot school’s VP, who, although he represented the main administrative oversight of the artists’ time in the school, was immensely supportive of the unusual needs of the production, and enthusiastic about its outcome. That this slightly surprised me, I think, only further reveals my own bias to expect fraught institutional relationships.

When I asked the VP some questions, he identified a key positive outcome of the project as the intergenerational connections created, similar to the outcomes outlined in Quinn and Kahne’s article. The performance involved bringing over 40 adults, including facilitating artists, performers, and volunteers, into the school, something I assumed would be alarming to administration. But, in fact, the VP told me he has been trying to set up intergenerational programming for students, through, for example, senior’s residences, but has never seen it have such genuine, positive, relational outcomes. I think this only supports Quinn and Kahne’s (2001) case that not only can taking part in “quality” (p. 14) art-making be “transformative” (p. 12), but this might be true particularly through the rarity of those intergenerational relationships, and the expertise in facilitating/building them that community-engaged artists bring (Hutcheson, 2017).

Adult Community Singers at What Was My Backyard? Performance

Next Steps

I’m now working on organizing evaluative material (from students, teachers, artists) and, from that, creating some curriculum guides and lessons plans that will be part of the package going to teachers/administrators who take part in future iterations of the show. I’ve also been involved in trying to make some connections to schools that might be future partners on the project, and it’s evident in these discussions how helpful documents like these would be both to help secure those new partnerships and apply for funding. In creating documents, guided by the evaluative feedback, I’m particularly interested in student and teacher responses to: What do you wish you had known before? I hope to create introductory lesson plans that respond to these desires, without losing the thread of creative discovery and surprise embedded in the process. It’s an interesting challenge to think through interactive activities that can be led by teachers (before the artists arrive) that might make this possible. And in all of this, my learning about partnerships feels really valuable, as the production team starts to try to envision the future of this project in new schools, with newer relationships to the team.

References

Quinn, T., & Kahne, J. (2001). Wide Awake to the World: The Arts and Urban Schools: Conflicts and Contributions of an after-School Program. Curriculum Inquiry, 31(1), 11-32. Retrieved January 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/3202291

Hutcheson, M. (2017). Framing Community – A Community-Engaged Art Workbook. Retrieved from http://www.arts.on.ca/oac/media/oac/Publications/Framing-Community-ACommunityEngaged-Art-Workbook.pdf